The Star of the Show

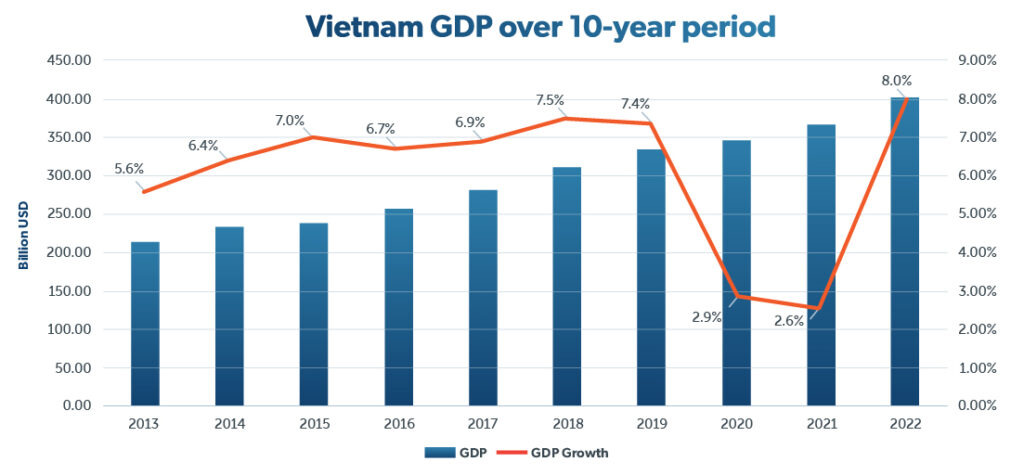

Vietnam wrapped up 2022 on a high note with an impressive GDP growth rate of 8%, the fastest pace in 25 years, and surpassed its official target of 6 – 6.5%.

Domestic consumption, export performance, and investment are driving growth. Domestic consumption and exports respectively stood at 15% and 41% higher than in the pre-pandemic year 2019. Registered foreign direct investment (FDI) capital in 2022 was the lowest since the beginning of the pandemic, estimated at USD 27.72 billion. However, realized FDI in 2022 stood at USD 22.4 billion, the highest in five years and a 13.5% increase from the previous year1. This shows that despite almost two years of pandemic-induced disruptions, foreign investors continue to favor the country.

Looking ahead, Vietnam is expected to sustain robust growth in 2023, albeit at a slightly slower pace of 6 – 7%.

Cleaning House

This year’s growth, however, might not come easily for the communist state. Besides unfolding global events such as the spectre of a global recession, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and U.S.-China tensions that may impact Vietnam and the world, there is an element of uncertainty from within.

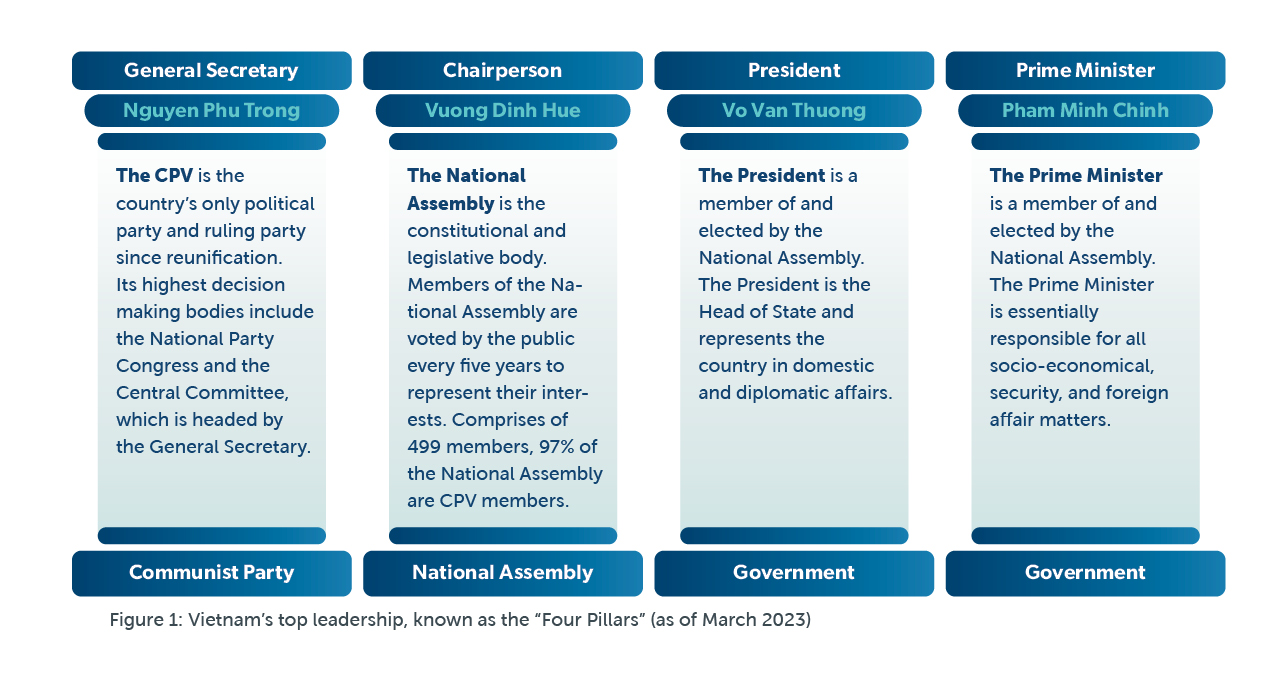

Many closely watch the reach of the “blazing furnace” anti-corruption drive spearheaded by Nguyen Phu Trong, the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV). Trong remarked at the drive’s 10-year mark in June 2022 that 16,000 corruption and corruption-related investigations were undertaken against over 30,000 defendants, including business executives as well as senior government officials. In particular, over 7,300 CPV members were disciplined, including four members of the Politburo, 29 members of the Central Committee, and 50 general officers in the People’s Army of Vietnam.2

On the upside, Vietnam’s ranking in Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index has improved significantly over the course of the anti-corruption campaign. In 2012, the country was ranked 123rd out of 176 countries and territories. Ten years later, it is rated 77th out of 180, behind only Singapore and Malaysia in the region. Coupled with the government’s continued efforts in streamlining the bureaucracy, this can help further attract foreign investment, which Vietnam’s economy heavily relies on.

But the crackdown has also shaken up key sectors of the economy and diminished the country’s position as a reliably stable body politic in the region. From 2017 to 2019, the real estate industry in Vietnam’s southern provinces was frozen as the crackdown intensified. Hundreds of real estate projects were investigated or suspended, and several government officials were implicated, including a former member of the Politburo and the most senior CPV leader in Ho Chi Minh City. In a similar vein, the ongoing investigation into a Covid-test kit scandal, which already saw two former ministers prosecuted, dominoed into supply disruptions and shortages of medical products. In both instances, government officials became too anxious to give the go-ahead for projects or procurements, fearing their approvals might later send them to jail.

In the private sector, arrests of several high-profile local corporate executives in 2022 have sent the country’s relatively nascent stock market into the red. Reuters in April 2022 estimated that the Vietnamese stock exchange lost USD 40 billion in market capitalization after the arrests of two of such executives in early 2022.3 Six months later, another high-profile executive who was long suspected of being backed by politicians was also arrested. Meanwhile, Pham Nhat Vuong, the owner of Vingroup and arguably the country’s most high-profile corporate executive, was rumoured to have been banned from travelling abroad by the police. All of them headed some of the country’s largest real estate companies, operating in what is considered one of the most corruption-prone industries.

Fanning the Embers

Such disruptions might be considered short-term, and for Trong, perhaps this is a price worth paying for the great cleanse. Since his rise to prominence in 2016 when he ousted the charismatic former Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung, Trong has been at the forefront of the country’s battle against corruption.

Observers have been unable to agree on Trong’s motivations. Some speculate that Trong is using the anti-corruption drive as a guise to remove his political rivals. Others view it as his attempt to re-assert the CPV’s power over the government apparatus, which is patronized by the private sector and gained influence during Dung’s premiership (2006 – 2016).

One thing is clear though: Trong, who considers “individualism” and “degeneration in political ideology and morality” as the root causes of corruption, will do everything in his power to make sure that the fire in the furnace will keep burning, even after he retires because of frail health.4 A recent reshuffle of top government officials is seen as a move by Trong to put in place, or expedite, his succession plan by inserting into the “four pillars” his “cleaner” and trusted ally who upholds the communist ideology.

What will rise from the ashes?

In early January, deputy prime ministers Pham Binh Minh and Vu Duc Dam were removed from their posts. This was quickly followed by the resignation of the President, Nguyen Xuan Phuc. The two former deputy prime ministers were caught up in Covid-19 related corruption scandals, one related to repatriation flights under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs where Minh was the minister, and another over Covid-19 test kits at the Ministry of Health for which Dam was responsible.

Phuc, viewed as a pro-business leader, was held accountable for the “violations and shortcomings” of senior officials under him, i.e Minh and Dam, when he was the Prime Minister (2016-2021). Many, however, believe the real reason for his ouster was because his wife was allegedly behind the company which paid a total of USD 33.7 million in kickbacks to provincial CDC centers for the purchase its Covid-19 test kits .5 This makes him the first President to voluntarily resign, and the highest-ranking official touched by the corruption crackdown. With Phuc out, Trong successfully installed one of his trusted cadres into the four pillars; Vo Van Thuong, whose spent his entire career inside the CPV, became the President in March.

Another shaky seat of the four pillars at the moment is the Prime Minister, Pham Minh Chinh. He is rumored to have backed a fugitive who has been sentenced a total of 30 years in prison for bid rigging and bribery in a hospital project.6

If Chinh is out this year, the two top positions in the Vietnamese government could be filled by entirely new faces. In addition to this, Trong, who has been in poor health for some years, is rumoured to be stepping down this year instead of completing his term in 2026.

Therefore, many are wondering:

- Who will replace Trong when he steps down? And what the new leadership will look like?

- Will anti-corruption efforts continue, and who will it reach?

Did you know?

Ho Chi Minh is not his birth name

Vietnam’s first President and Prime Minister, Ho Chi Minh, was born as Nguyen Sinh Cung in 1890. Throughout the years of revolutionary and political activities, he used over 160 pseudonyms. The name Ho Chi Minh was first used around 1942.

1 Registered FDI is the investment capital that foreign investors lodge with the Ministry of Planning and Investment; this includes fresh registered capital for specific projects, revised registered capital from previous years, and registered capital for partnership with or acquisition into Vietnam-based companies. Realized or disbursed FDI is the actual capital being spent on projects and business activities within the year.

2 The CPV’s highest leadership body is the National Party Congress, which convenes every five years. During the five years between the two congresses, the Central Committee is the decision maker within the CPV. The Central Committee comprises of the CPV’s most powerful members. The Politburo, of which members are elected by the Central Committee, is primarily responsible for the implementation of resolutions passed by the Party Congress and Central Committee.

3 https://www.reuters.com/article/vietnam-security-markets-idUKL3N2WP3M0

4 https://www.asiasentinel.com/p/nguyen-phu-trong-legacy

5 https://www.channelnewsasia.com/asia/vietnam-president-phuc-resigns-corruption-wife-covid-test-kits-scandals-3219991

6 https://fulcrum.sg/red-card-for-the-president-vietnams-biggest-political-drama-in-decades/